07775 853 348

Every winter enthusiast should incorporate avalanche safety and awareness planning. Even the most experienced climber in the world cannot pretend to predict every avalanche. Nonetheless, avalanches are not supernatural events. By understanding the science of snow and how avalanches form, we can give ourselves the best chance of reading warning signals and reducing the threat they pose.

Let’s begin with a general description of snow and the types of avalanches.

AVALANCHE SAFETY AND AWARENESS CONSIDERATIONS:

- Terrain

- Snowpack

- Weather

- Planning beforehand

- Whilst out on your journey

- Key places

- Flexibility in your objectives

SNOW STELLAR CRYSTAL

Snow forms in the atmosphere where super-cooled water droplets condense around microscopic particles such as dust and plant spores. As water vapour freezes around these nuclei, snow crystals are formed. These are generally hexagonal (see picture), but they can also be plates, columns and needles.

The shape and form of the crystals are largely determined by the temperature and humidity at their formation and on their journey through the atmosphere.

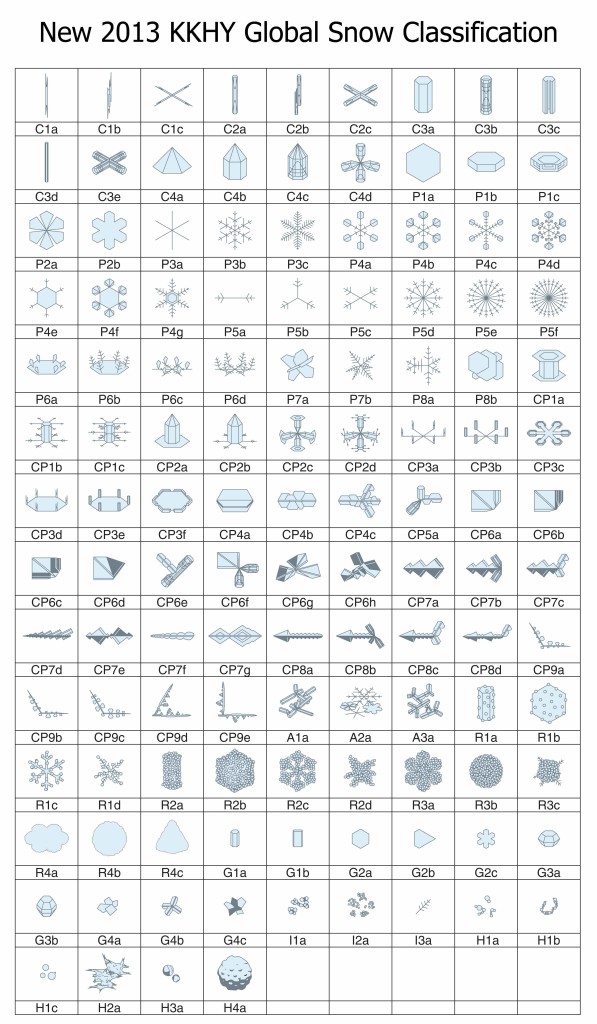

Here you can see a list of the 121 different types of crystals that are formed in our atmosphere.

HOW DOES SNOW CHANGE SHAPE?

Once the snow crystals have fallen to the ground, there are several ways these will change shape.

Dry snow metamorphism or rounding

– this is where the branched snow crystals become rounded over time as water sublimates (changes from a solid state to vapour, back to solid)

Kinetic growth or faceting

– caused through the difference in temperature from the bottom of the snowpack (0°C), and the surface temperature. The bigger the temperature difference per cm, the greater the vertical migration of water vapour through the snowpack.

Melt-freeze metamorphism

– in thaw conditions practically all snow crystals are reduced to rounded ice grains surrounded by a film of liquid water. A subsequent freeze will cement these grains together.

Wind transportation

– winds in excess of 20mph will cause damage to the snow crystals. Broken crystals tend to be dumped in areas where the wind is decelerating (leeward side of a hill).

TYPES OF AVALANCHES – SIMPLIFIED

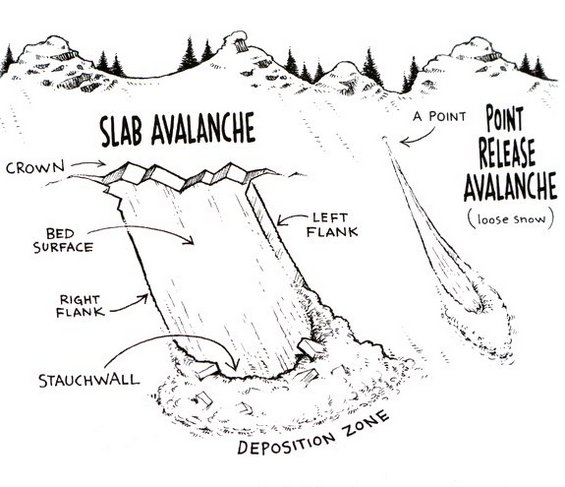

Loose snow avalanches are usually characterised as a point release or a slough, and involve unconsolidated layers of surface snow. Slab avalanches occur when one or more layers of cohesive snow release as a unit.